Go vs. Rust

Introduction

I'm a Data Engineer with extensive experience in Python and SQL. At Hemnet, I work in the Data and Machine Learning team, where we build a robust data platform and educate teammates on effective data use.

Funny, but today I won't talk about Python or data engineering. A year ago we started developing an events proxy in Go as a R&D project. We chose Go for simplicity, compiled-language speed, and proven track record running backend services. Hemnet's LLM-services usage policy helped us here a lot. Developers can use anything: Claude Code, ChatGPT, Gemini, GitHub Copilot, and their coding agents with minimal restrictions — just don't leak sensitive data in prompts. No one on our team knew Go back then. We dove into vibe-coding the service and then polished the result.

Later I wanted to practice Rust skills and got an idea: rewrite this app in Rust and compare performance. Now I have observations, struggles, pleasures, and performance numbers to share. Even though I knew some Rust, I used vibe-coding heavily here as well, since I never built a backend service in Rust before.

Developer Experience

This article is highly subjective and unfair to Go. I spent a year learning Rust: read "The book", solved all Rustlings — yet still felt insecure writing Rust. On the other hand, I never even read a line of a Go code. If I had learned Go properly, I might be more positive about it. Maybe not. Keep this in mind when I complain about Go.

Both Go and Rust are compiled and statically-typed languages, but differ in many aspects. Their official website statements reflect this well:

Go promises simplicity and mature ecosystem

Rust promises performance and reliability

Go strengths

Cleanest syntax ever. No semicolons at line ends, no colons between arguments and types, no lets — pure meaningful symbols. The only thing that could be cleaner would be using Python's indents instead of curly braces. All visual noise was thrown away, making language readable and easy to learn. Python and Go are similar in this approach.

// Shutdown gracefully stops the metrics collector.

func (mc *MetricsCollector) Shutdown() {

close(mc.done)

mc.ticker.Stop()

mc.wg.Wait()

mc.statsd.Close()

}

Easy language to learn. It favors imperative commands over functional approach, no inheritance on classes. Channels and goroutines are the only syntax features you need to learn, but they are simple to use unless you need granular control over them.

Rich stdlib for networking/backend apps. When we finished our app, we had only go-redis, sentry-go, dd-trace-go (DataDog), go-env, testify dependencies, which is relatively small list of dependencies. Stdlib includes lots of batteries: http server, structured logs, date, time, json, parallelism, async, io streams and more.

Mature ecosystem. You'll find almost all libraries you need for development as long as you stay in domains Go shines in.

Go weaknesses

When I hear "statically typed compiled language", I expect the compiler to check the program can run and prevent silly mistakes. Go won't do that in lots of cases, unless you install third-party linters (sometimes even with them).

For example, you can compare a type instance with an alias of the same type and compiler happily compiles it. Then at runtime, you'll always get a negative result, even if contents are equal.

package main

import (

"reflect"

"testing"

"github.com/stretchr/testify/assert"

)

func TestEqualityTypes(t *testing.T) {

type Event map[string]any

m := map[string]any{"user_id": "123"}

e := Event{"user_id": "123"}

assert.True(t, reflect.DeepEqual(m, map[string]any(e)))

assert.True(t, reflect.DeepEqual(m, e)) // surprisingly `False`

}

Manual management of parallelism. Go claims its parallelism system as easy and lightweight. It's true, unless you need minimal control. Here's an example.

Running parallel code with goroutines requires working groups to ensure all threads finish before you proceed. With sync.WaitGroup it's easy to forget calling .Done() or mis-balance Add/Done — which leads to deadlocks or panics.

As of Go 1.25 this is solved with wg.Go() function, but it's surprising how long the language lacked such a basic tool.

Default values for everything. C is famous for unexpected behavior when you forget to initialize variables — resulting in a random garbage from memory as a variable value. Go fixed this by setting defaults for every type at declaration time. Sounds better, but that just moved unexpected behavior one level further — to developer.

Imagine structure S with fields a str, b str. You instantiate it with S{a: "a", b: "b"} expression in multiple places, then decide to add a third field c str to the struct. If you forget to update your code, you'll get silent default empty string S{a: "a", b: "b", c: ""} instead of a compilation error and conscious developer's fix. One of the worst language design decisions in my opinion.

Absence of basic functions. I am used to having min(), iterator functions, and other functional primitives built into a language. Go lacked a built-in min() until version 1.21, and it still lacks standard map, filter implementations. Features available in Rust and Python are missing here — you'll write your own for loops and comparisons instead.

if err != nil. That's a language signature, isn't it 😀? Whenever I see if err != nil, I know it's Golang. It feels a shame to have such clean syntax and be forced to put these boilerplate error constructs, taking the place of actual logic.

No fun with it. Yes, that's totally subjective, but I've heard this complaint from other developers as well: no joy writing Go. Maybe it's too simple and does not provide enough cognitive tasks to solve itself, maybe I am irritated from the cons above.

Rust strengths

Compile-time guarantees. It's a stretch to say "if it compiles, it doesn't have bugs", but it's as close as it could be. Rust provides elegant tools to handle errors and optional values with Result, Option enums and ? operator, so you can't get the value without deciding how to deal with possible errors. There are no uninitialized variables, as this is checked compile time. There are no accidental mutations for variables that are not supposed to be mut.

It's a different experience from Python, where programs I write never work from the first try. Same in Rust, but I get to know all errors from LSP instead of runtime exceptions.

cargo cult. It's not something bad in Rust. It has builtin cargo cli tool, which combines package manager for loading libraries, test runner, compiler, executor, linter, formatter — everything a modern developer needs. Even if Rust dies today, the influence it made by its cargo example to other languages (e.g., uv for Python) is invaluable.

Tests are first-class citizens.

Following the Rust best practices, tests live in the same file as code. That felt controversial at first. I like test-driven development, but 90% of the time I'm too lazy to follow it. Why overwhelm long enough code with tests?

I valued it later. This approach works in many ways: you stop treating test code as second-class citizen, you get the right perception of code complexity when you're adding the 1000th line of tests, you finally don't forget tests exist. Coding agents won't miss tests as well during code writing and will fix inconsistencies. And I didn't even touch the doc-string code tests that work out of the box yet.

No data races. Ownership and borrowing aren't the easiest concepts to deal with, but they put you in the right way of thinking about your variables. The compiler makes data race conditions impossible, even with parallelism or async execution. Annoying at first, then you become grateful as compiler prevents problems from the start.

Joy. I have joy writing Rust. It's somewhat masochistic pleasure — hard to satisfy the compiler with trait bounds and borrowing rules, but relieving when you solve it and know you did the right thing.

Performance. I put it last because for me this advantage doesn't play a big role — I don't write performance-critical code regularly. But it's good to know that I have a tool to make one if needed.

It's especially cool that it's easy to write a function in Rust and compile it to a Python package using maturin (5-20 additional lines, well documented library).

Rust weaknesses

Complex language. Many concepts must be mastered to write Rust: ownership and borrowing, lifetimes, absence of garbage collector, traits and trait bounds, Enums and pattern matching, complex syntax using every keyboard character <&[(*)]>?, mut modifier on variables, pattern matching in function definitions (arg1: &Type, _: Type, &arg2: &Type), macros, tail expressions, functional programming. All that makes Rust's learning curve steep.

Immature ecosystem. That's where you feel Rust is still growing. Most likely you'll find everything you need to write your code and cover most popular cases, but when you go outside those, you face the need to write your own features. For example, there is still no official DataDog library (even though it's developing right now), so you're forced to use third-party solutions which don't cover everything, e.g., sending metrics. You're able to compose it with other libraries, but it's not out of the box as in Go or Python.

Many libraries to choose from. This might sound contradictory to the previous point, but when it comes to common things like web-server framework, there are plenty of libraries. For example, for web framework you may choose from Axum, Rocket, and Actix — they have similar GitHub stars and functionality, so you need to spend some time on investigation as there is no "golden way". That won't be a big problem if Rust had as rich stdlib as Go, but in fact it's the most simplistic stdlib I've ever seen. You'd install third-party libraries for async traits, error propagation, logging, http requests, jsons, etc.

Too many ways to do things. On the other hand, Rust has an exhaustive set of methods on different types... And this abundance of methods could be a cognitive problem. For example, `Iterator` has 75 associated methods, some of them doing similar things, but not exactly the same. It could be hard — I’m not even saying to learn them all (I gave up) — but even to choose from the completion list which one you need. cargo clippy linter helps a bit: it may suggest using another method if it finds your function call suboptimal, but it's still not easy to pick the right one. And it's not only about iterators: Result, Option enums and other commonly used structs have their own excessive method lists.

Making generic code can be a nightmare. Maintaining code containing pipes of generic functions is not easy in its own. Maintaining code containing generics and trait bounds could be ten times as hard, because on one side, trait bounds are close to interfaces/protocols/types, but they're still different, and some of them are just a product of compiler's magic checks. Here's a relatively simple example from the Redis library that still hurts to read:

pub trait AsyncTypedCommands

pub fn xinfo_groups<'a, K>(&'a mut self, key: K) -> crate::types::RedisFuture<'a, streams::StreamInfoGroupsReply>

where

K: ToRedisArgs + Send + Sync + 'a,

// Bounds from trait:

Self: crate::aio::ConnectionLike + Send + Sized,

Performance

Now let's see how these developer experience differences translate to actual performance.

The app receives JSON events via HTTP, validates them, and writes them to Redis Streams. To test the performance I made a docker compose setup including two services: valkey (open-source version of Redis, supporting Redis Streams) and the app itself (Go or Rust version). Apps are limited to 2 CPUs and 1 GB of memory (however, as you'll see, 50 MB would be more than enough for the services). Both apps used debian:bookworm-slim as runtime docker image, executing binaries from the build stage. Rust used version 1.92, Go — 1.25.

# docker-compose.yml

services:

collector:

image: rust-collector / go-collector

build:

context: .

env_file: .env

depends_on:

valkey:

condition: service_healthy

ports: ["8080:8080"]

mem_limit: 1g

cpus: 2

valkey:

image: valkey/valkey:8

container_name: valkey

ports: ["6379:6379"]

healthcheck:

test: ["CMD-SHELL", "redis-cli ping | grep PONG"]

interval: 10s

timeout: 5s

retries: 3

volumes: [valkey:/data]

Load was generated by another Rust app locally and sent to the docker compose service app. First I made it build random jsons every time using faker to avoid possible execution optimization for repetitive hot paths, but then I found that the load generator itself got stuck at generating 420k events — good result, but not helpful when your Rust app handles up to 500k. So I changed it to be random but repetitive, creating a batch of 100 events and then repeating it, which helped to bump load generator's performance up to 800k/s.

Apps were tested by incrementing the number of load threads as follows: [1, 4, 16, 64].

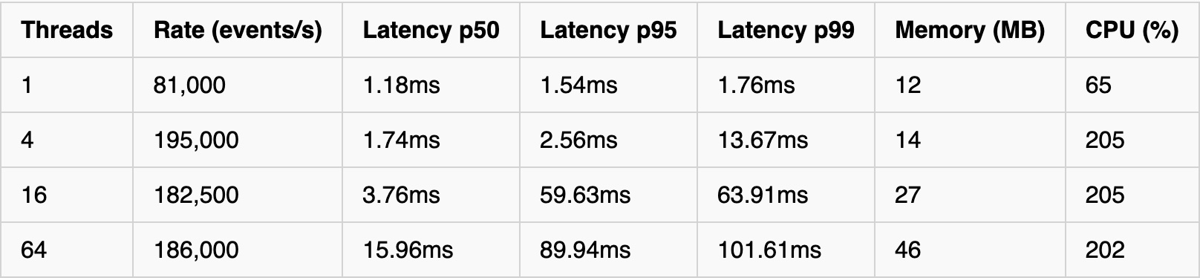

Go results

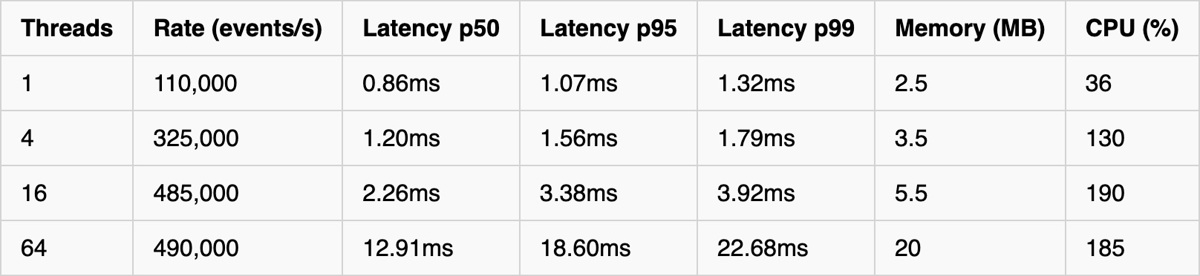

Rust results

Both Go and Rust deliver on their promises as compiled, statically-typed languages for backend services, but it's clear that Rust outperforms Go.

In this test, Rust delivered ~2.5x higher throughput (490k vs 185k events/s at peak), ~3-5x lower memory usage, and more stable latency under the high load. Go's latency degraded dramatically at 16+ threads (p95: 60ms vs 3.4ms), but was better at low volume of load.

Final thoughts

Does this test prove Rust is better than Go? Yes for isolated performance. No, if we take the language holistically.

My personal preference clearly lies towards Rust, but I see opportunities in using Go. It would be exhaustingly hard to learn Rust as a first language for most beginning developers, while Go seems a good choice as a first language along with Python.

From the agentic writing perspective, not much difference in writing both languages. They're both well known and supported by modern LLMs.

Rust is harder to write and read even if you've mastered it. Absence of some libraries complicates the situation. On the other hand, reliability is the prize.

From the career perspective, with all the Rust growth in recent years, it's still hard to find a job as a Rust developer, which is not the case for Go. That may change in the future, but it seems to be quite inert.

I believe you should use the language you enjoy — doesn't matter if it's Python, Go, Rust or (even) Haskell. If you have fun with it, you'll master it, be more productive and happy.